'Tis the season! And oh how I love it … as the six crates of Christmas decorations wedged into every nook and cranny of my too-small California garage testify. And when I haul out those bins every year, I’m well aware that the berries and bows that will decorate my front door, the twinkling lights for our tree, and the (oh so special) gingerbread man mugs for the first hot chocolate of the season have absolutely nothing to do with the Nativity. And I’m ok with that. But what about my actual Nativity?

Or should I say my six nativities? There is the stuffed nativity whose characters were often tucked into bed with rosy cheeked toddlers. The delightful resin one that my girls spent hours and hours rearranging during their elementary years (such that none of the characters have hands anymore … and that poor angel who gets her wing glued back on every year). The handmade Shaker set that embodies simplicity. And the most precious (and breakable) of all that sits on our mantel every year. It was a costly gift from my husband early in our marriage, and it is the first decoration to go up, and the last to come down. Is this decoration a reasonable representation of the very first Christmas eve? Ok, I realize that it might just be folk like me who focus on such obscure concerns, but I was pretty confident that folk like you would want to know what my conclusions were.

As I discuss in The Epic of Eden: A Christian Entry into the Old Testament, the integration of data gathered via archaeology, modern ethnographic study, and the biblical text leaves us with a surprisingly clear picture of what the living quarters of a first century Judean family looked like. And in gathering this information, we also get a surprisingly clear image of what the first Christmas may have looked like as well.

You know the tale. Our young and ostracized couple have found themselves far from home, taking temporary residence in the town of Bethlehem due to Caesar Augustus' declaration that a census would be taken. Joseph, a son of Bethlehem, has brought his fledgling family the long 90 miles south from Nazareth. In Israel’s patrilineal society, Joseph and his family should have found shelter with his extended family. But for reasons that are unclear—perhaps the social fragmentation of the Exile, or that Joseph's kin had been long departed from Bethlehem, or perhaps the scandalous nature of his marriage—no kinsmen offered hospitality to this young family.

And so the Gospel-writer tells us: "6While they were there, the time came for the baby to be born, and she gave birth to her firstborn, a son. She wrapped him in cloths and placed him in a manger, because there was no room for them in the inn" (Luke 2:6-7, NIV 1984). There is great debate as to what sort of "room" is unavailable—is it a room for rent at an inn, the guest room of a kinsman's house—we don't have enough data to be sure. We do know the result, however. Our sweet, courageous Mary lays her firstborn in a feeding trough. And we citizens of this fallen world wince as we ponder what sort of welcome we offered to the Prince of heaven.

So where was this feeding trough? Your manger set and mine picture the scene with European eyes. Hence our manger is made of wood, it is located in a barn also made of wood (with a pitched roof for snow by the way!), and the scene is animated by a collection of creatures that would make Old MacDonald proud. But is that really what Mary and Joseph were experiencing?

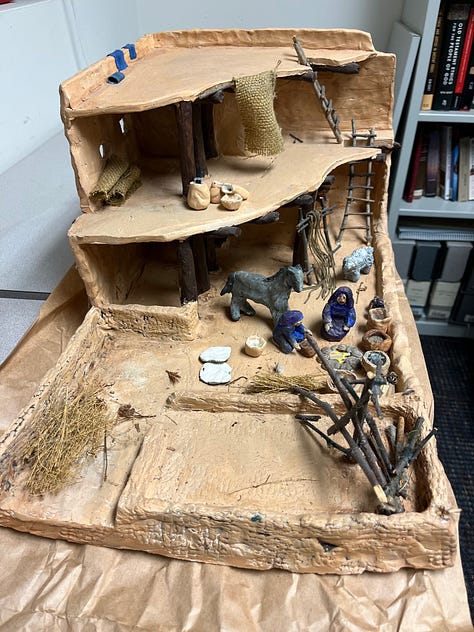

It was my professor of archaeology at Harvard University, Lawrence Stager, who first brought the details of the Nativity to my attention. As we had studied in our various classes, and excavated more than once, the standard "three bedroom ranch" (or "two bedroom Cape" depending on what part of the country you're from) was, in Israel, the "four-room pillared house." These houses fit the lifestyle of our Palestinian peeps, were relatively easy to build, suited the topography, and the building supplies were readily accessible. Thus, we have evidence that this architectural style—pictured above via a past student project—dominated residential areas from the influx of the Israelites in 1200 BCE through every era of their occupation of the land. In rural settings several of these would be found within a standard "family compound," set apart by a low wall marking the division of human habitat from the fields and flocks that supported the family farm. In more crowded, urban settings, like Bethlehem, these houses were more like townhouses—sharing their exterior walls, with their rear walls sometimes doing double-duty as the wall around the village.1 This typical Israelite home had two-stories, each of which with three long rooms delineated by rows of pillars, and a long room which spanned the back of the house. The house was constructed of a mixture of field stone and mud brick, sealed and plastered. The roof was composed of small branches, plastered together with eight to ten inches of tempered clay and mud and/or sod, all of which required a great deal of maintenance. And like any 200-year-old house in Wheaton IL or Newburyport MA, folks added to these houses as the need arose, and sometimes the original core of the house took an archaeologist to locate!

So why do we care? Well, we are quite certain at this point that it was the second floor of the house that served as both dining and bedroom. The family members ate, slept, and entertained on the second floor, and during good weather, the roof as well (cf. 1 Sam 9:25-26; 1 Kgs 17:19, cf. Acts 1:13). The first floor? The central room was an open courtyard used for cooking, weaving, and other household chores. The rear room was where the enormous collared rim storage jars holding wine, water, and oil were kept as well as pits dug into the floor as grain silos.2 And what about the side rooms of the first floor? This is where it gets interesting. These side rooms functioned as stables. We know this both because the floors were cobbled (to help urine dissipate), and the rooms were set apart by stone feeding-troughs. This warm, protected space was ideal for young or vulnerable animals; livestock about to birth; and the “stall-fed calf” being fattened up for the feast (1 Sam 28:24).3 And although the aroma of this shared habitat might be less than ideal, the animals’ presence on the first floor of the house provided the family with a cheap source of central heat.

It is this well-known house design that inspired Stager to propose that the story of Jesus’ birth in Bethlehem had nothing to do with a stable (or cave) down the street. Rather, when a desperate young husband comes knocking on that inn keeper's door, the response was likely far less inhospitable than we have imagined. I can hear the man now. "Sir, I am so sorry. I do not have one square inch of space left on the second floor, or even on the roof. But I do have an empty stall here on the first floor. It's not ideal, I know. But at least it is warm, and private, and my wife will be close at hand if there is trouble. You are welcome to it."

In sum, it is highly unlikely that Jesus' first cradle was a wooden manger in a free standing barn. Rather, our Prince of Peace was likely laid in the stone feeding-trough on the first floor of a first century four-room-pillared house. Ideal? No. But neither was the Incarnation. Rather this one, being in very nature God, made himself nothing, “being made in human likeness," and in his grace he came to us as we are … not yet as we should be.

O little town of Bethlehem

How still we see thee lie

Above thy deep and dreamless sleep

The silent stars go by

Yet in thy dark streets shineth

The everlasting light

The hopes and fears of all the years

Are met in thee tonight

Excerpt from The Epic of Eden: A Christian Entry into the Old Testament (pp. 34-37). Purchase your copy of the book here.

See Larry G. Herr and Douglas R. Clark, “Excavating the Tribe of Reuben” BAR 27:02 (Mar/April 2001).

Philip King and Lawrence Stager, Life in Biblical Israel (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2001), 35-38.

Stager, “The Archaeology of the Family in Ancient Israel,” BASOR 260 (1985), 15.

So interesting! Thank you.